So whats the next word, then?

Posted | Reading time: 13 minutes and 22 seconds.

Contents

My kids are pretty much required to endure some kind of tech explanation whenever they ask me what I do at work. Last Tuesday my kid came back from school, sat down and asked: “How does ChatGPT actually know what word comes next?” And I thought - great question. Terrible timing, because dinner was almost ready, but great question.

So I tried to explain it. And failed. Not because it is impossibly hard, but because the usual explanations are either “it is just matrix multiplication” (true but useless) or “it uses attention mechanisms” (cool name, zero information). Neither of those helps a 12-year-old. Or, honestly, most adults. Also, even getting to start my explanation was taking longer than a tiktok, so my kid lost attention span before I could even say “matrix multiplication”. I needed something more visual. More interactive. More fun.

So here is the version I wish I had at dinner. With drawings. And things you can click on. Because when everything seems abstract, playing with the actual numbers can bring some light.

The problem: reading one word at a time

Before Transformers existed, AI read sentences the way you would listen to a podcast at 3x speed, desperately trying to remember what was said five seconds ago while new stuff keeps coming in.

Imagine reading “My sister picked up the guitar that she bought in Vienna and started playing because she missed home”. By the time you reach “she missed home”, you need to remember that “she” is your sister, that this is about a guitar from Vienna, and that playing it is tied to an emotion. You and I just know all of this; but a computer reading word-by-word has basically forgotten “sister” by the time it reaches the end. It is like trying to remember the first item on a shopping list after reading 200 more items.

This is what Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) did. They were the hot thing back when I was in University. And I’m almost a boomer. So for short sentences they were fine. For longer ones? They forgot things. A lot.

In 2017, a team at Google said: what if instead of reading one word at a time, the computer could look at all the words at once and figure out which ones are important to each other? They called their paper “Attention Is All You Need”1. Bit of a bold title for a long paper that kinda said you need a lot of things, if you ask me. Well, but asking me they didn’t. So there’s that. Every AI chatbot you use today - ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, even the crappy ones from Amazon - is built on this idea.

Let us build it up, piece by piece.

Step 1: turning words into numbers

Computers do not understand words. They understand numbers. And really only two of them, but that’s a different story. So the first thing we need is a way to turn every word into a list of numbers - a vector. Think of it as GPS coordinates, but instead of two numbers (latitude, longitude), you might have 512 or even thousands of numbers describing where a word sits in “meaning space”.

Words with similar meanings end up close together. “Pizza” and “pasta” are neighbours. “Pizza” and “database” are very far apart.

The best part about it is these vectors are not hand-crafted by humans. The model learns them during training, just by reading enormous amounts of stolen text. It figures out on its own that “king” and “queen” are related in a similar way as “man” and “woman”.

Interlude: Why this changes everything about search

Let me tell you why this embeddings idea is such a big deal beyond just chatbots. Think about how search worked before: you typed “cheap flights to Italy” and the search engine looked for pages that contained those exact words. If a page said “affordable airfare to Rome” (which is basically the same thing) the old systems other and before then google missed it. Word for word matching, like a very literal robot.

Now, with embeddings, the search engine converts your question and every document into vectors - those lists of numbers we just talked about. Then it does not look for matching words anymore. It looks for vectors that are close together in meaning space. “Cheap flights to Italy” and “affordable airfare to Rome” end up as neighbours, because the model learned that “cheap” and “affordable” live in the same neighbourhood, and “Italy” and “Rome” are obviously related.

The way you measure “closeness” is called cosine similarity. Yeah I know, a math term and you’re at “boooring”, but bear with me. Imagine two arrows pointing from the origin in different directions. If they point the same way, the angle between them is small: they are similar. If they point in opposite directions, they are very different. Cosine similarity measures exactly that angle.

This is how modern search engines, recommendation systems, and even that “find similar images” feature on your phone work. It is also the backbone of RAG ( Retrieval Augmented Generation) which is the fancy name for “let the AI search a knowledge base before answering”. Instead of memorizing every fact (and getting some wrong), the AI embeds your question, finds the most relevant documents by vector similarity, reads those, and then answers. Like a student who is allowed to use their textbook during the exam. Which is a much better way to do it, if you ask me. (And they didn’t, again, ask me they didn’t)

The horrible truth is that even with all this, search still is not perfect. Vectors are approximations of meaning, not meaning itself. But they are dramatically better than keyword matching, and they are the reason you can type a vague question into a search bar and still get useful results.

Step 2: where are you in the sentence?

Here is a problem: if we feed all words into the system at once (instead of one-by-one), how does the computer know what order they are in? “Arduino controls LED” and “LED controls Arduino” have the same words but very different meanings. (Trust me, the second one is not what you want)

The solution is clever: we add a special pattern of numbers to each word that encodes its position. And these patterns use sine and cosine waves - yes, the same waves from maths class.

Why waves? Because waves at different frequencies create unique patterns for each position. Position 1 gets one pattern, position 2 gets a different one, position 247 gets yet another. And here is the really neat bit - the model can figure out that position 5 is “3 steps after position 2” because the waves have a mathematical relationship. It is like giving each word a musical chord that tells you exactly where it sits.

Step 3: attention - the heart of everything

This is where it gets good. When people talk about Transformers, this is what they are really talking about.

The idea: for every word in a sentence, the model asks “which other words should I pay attention to, in order to understand this word better?”

Take the sentence: “My sister picked up the guitar and started playing because she missed home”.

When processing “she”, the model needs to figure out that “she” refers to “sister”, not “guitar” or “home”. It does this by computing an attention score between “she” and every other word. High score = “these words are related”. Low score = “not really connected”.

Interlude: How it actually works: Q, K, V

The model creates three different versions of each word:

Key (K) - "What do I contain?"

Value (V) - "What information do I actually carry?"

Think of it like a library. The Query is your question (“I need a book about space”). The Key is what is written on the spine of each book (“Stars and Galaxies”, “Italian Cooking”, “Black Holes for Beginners”). The Value is the actual content of the book.

You compare your Query against all the Keys to find the best matches, then read the Values of the matching books. That is attention in a nutshell.

The maths: you multiply each Query with each Key (a dot product), divide by a scaling factor so the numbers do not explode, then use something called Softmax to turn the scores into percentages that add up to 100%.

That Softmax step is important. It takes a bunch of raw scores and turns them into a probability distribution - which is a fancy way of saying “percentages that add up to 1”. The highest scores get way more than their fair share, and the tiny ones get squished down to almost zero. Softmax amplifies winners.

Step 4: multiple heads are better than one

Here is something I find oddly satisfying. Instead of having one attention mechanism, Transformers use several in parallel - called Multi-Head Attention. Each head learns to look for different things.

One head might learn grammar relationships (“my” goes with “sister”). Another might learn meaning relationships (“playing” relates to “guitar”). A third might track who is who (“she” refers to “sister”). It is like having a team of specialists instead of one generalist.

In GPT-style models, you might have 96 attention heads working in parallel across 96 layers. That is a lot of specialists looking at your sentence from different angles.

Step 5: the feed-forward bit

After attention figures out which words relate to each other, the result goes through a small neural network applied to each position independently. Think of it as a processing step that says “ok, now that I know ‘she’ is related to ‘sister’, let me think about what that means for the rest of the sentence”.

This network expands the data to a bigger space (usually 4x bigger), applies a function that throws away negative values (called ReLU - it is literally just max(0, x)), then shrinks it back down.

Simple enough to be built by a kid lying on a couch with fever. And yet, stacking these layers is what gives Transformers their power.

Step 6: stacking it all together

One Transformer layer = Attention + Feed-Forward. A real model stacks dozens or even a hundred of these layers on top of each other. Each layer refines the understanding a little more.

There are two more tricks that make it all work:

Layer Normalization: After each step, the numbers get normalized (shifted so their average is 0, scaled so their spread is 1). This keeps the numbers from growing out of control as they pass through many layers.

Step 7: predicting the next word

After all those layers, the final output for each position is a vector. To turn that back into a word prediction, the model multiplies it by the embedding matrix (remember step 1?) to get a score for every word in its vocabulary. Then Softmax turns those scores into probabilities.

If the sentence so far is “My sister picked up the”, the model might give “guitar” a 15% probability, “phone” a 12% probability, “book” 8%, and so on across its entire vocabulary of around 50,000 words.

It then picks one. Sometimes it picks the most likely one. Sometimes it picks randomly-ish, weighted by the probabilities - which is why you get different answers if you ask the same question twice. That randomness is controlled by a setting called temperature. Low temperature = predictable. High temperature = creative (or chaotic).

The elephant in the room: why AI makes things up

Let us face it. If you have used ChatGPT for more than five minutes, you have caught it confidently stating something completely wrong. My daughter’s experience: she used it to learn history for her class, and when I test her she came up with the new german history that ChatGPT invented, where the German Reich already came from the Revolution of the german people in the year 1848. Presented with the confidence of a Wikipedia article. Entirely fiction.

This is not a bug. This is the architecture. And now that you understand how Transformers work, you can see exactly why.

Go back to Step 7. The model predicts the next word by computing probabilities across its entire vocabulary. It picks “the word most likely to come next given everything before it”. Not “the word that is true”. Not “the word that corresponds to a fact in a database”. Just: what word would a human probably write here?

The model has no internal fact-checker. There is no module that says “wait, is this actually true?” There is no database it looks up. It is just pattern completion - extraordinarily sophisticated pattern completion, but pattern completion all the same.

The multiplication problem: non-deterministic agents

Everything above explains why these systems wobble. The output is a probability distribution, and the model samples from it. That is great for creative tasks, but terrible for repeatable workflows. Ask the same prompt twice and you can get two different answers. In an agentic setting, every step is a probabilistic guess, not a guaranteed result.

If a workflow has many steps, those probabilities compound. If each step is correct with P = 0.99, then a 10-step workflow succeeds with 0.99^10 (0.90%) which is still okayish, but a 100-step workflow succeeds with 0.99^100 (37%) which is kinda badish.

And most models today are far below 0.99 for real-world tasks. That is why unattended agents are risky, and why you should be skeptical of any promise that sounds like “set it and forget it”, because they might just delete your computer. I wrote about this in more detail in “Why non-deterministic AI agents are a problem for enterprise”.2

Why confidence does not mean correctness

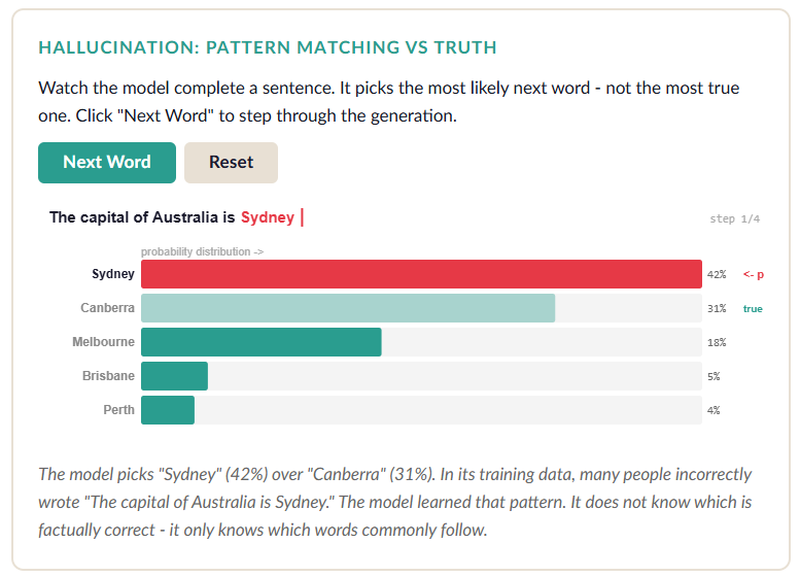

Here is the really tricky part. When the model is wrong, it does not “feel” less confident. The probability distribution for “The capital of France is ___” gives “Paris” 95%. Great, that is correct. But “The capital of Australia is ___” might give “Sydney” 40% and “Canberra” 35%. The model will happily write “Sydney” with the same confident tone it used for “Paris” - because it is just predicting what text commonly follows those words.

In its training data, plenty of people have written “The capital of Australia is Sydney” (they are wrong, but they wrote it, and they too are probably confident about it. That’s what people do, not a bit better then LLMs actually). The model learned that pattern. It does not know the difference between a correct statement it saw 10,000 times and an incorrect statement it saw 5,000 times. Both are just patterns.

It gets worse: the knowledge is baked in

All the “knowledge” a Transformer has is encoded in its weight matrices - those millions (or billions) of numbers that were set during training. When you ask it a question, it does not go look something up. It reconstructs an answer from compressed statistical patterns. Think of it like this: if you memorized every cookbook in the world but then someone asked you “what temperature for roasting a chicken?” - you would reconstruct an answer from all those overlapping memories. Most of the time you would be right. But sometimes your memories would blend together and you would confidently say “180C for 3 hours” when the actual answer depends on the size of the chicken. You would have no way to check, because the cookbooks are gone - only your compressed memory remains.

That is why the search + embeddings approach from earlier matters so much. RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) is essentially saying: “Do not trust your memory alone. Before answering, go find the actual document, read it, and base your answer on that”. It does not completely solve hallucinations, but it dramatically reduces them for factual questions.

Technology moves on. And the maths behind it is surprisingly elegant once you see it piece by piece. No magic. Just linear algebra, some sine waves, and a lot of clever engineering by people who asked “what if we just let the model look at everything at once?”

And if you want to dive deeper, I highly recommend Dr. Michael Stal’s article on the mathematics behind Transformers3. It is a fantastic resource that goes into much more detail than I can cover here.

But a thing we also have to remember: no understanding. No knowledge. No truth-checking. Just really, really good pattern matching. And that is both the beauty and the limitation.

Now if you will excuse me, I have to explain gradient descent to a 12-year-old before bedtime. Wish me luck.

-

“Attention Is All You Need” by Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, Illia Polosukhin. Published in 2017. The paper that introduced the Transformer architecture. ↩︎

-

“Why non-deterministic AI agents are a problem for enterprise” by Matthias Kainer. ↩︎

-

“Large Language Models: Die Mathematik hinter Transformern” by Dr. Michael Stal. ↩︎