Making remote leadership work Part III: Working with individuals – helping the face behind the chat window

Posted | Reading time: 17 minutes and 56 seconds.

Contents

A horror story of remote management

It was a typical Monday morning, and one of the software teams at Contoso company was logging into their computers to start the workweek. Thanks to Covid, for the first time fully remote.

Their leader, Sarah, had always been a strong and confident manager, but she struggled with the transition to remote work. She had always been used to walking around the office, checking in with her team, holding impromptu meetings whenever needed, or having a quick coffee or pairing session if she noticed a person was stuck. Now, Sarah felt disconnected and out of touch with everyone.

As the day went on, Sarah found it increasingly difficult to communicate with her team and ensure everyone was on the same page. She was used to being able to read body language and facial expressions, but over video calls, it was harder to gauge how people were feeling. Sarah also struggled with running the meetings, and the one on ones she had with her team felt like a complete waste of time.

By the end of the day, Sarah was feeling overwhelmed and frustrated. She had a long list of tasks that needed to be completed, but she was having trouble coordinating with her team members and ensuring that everything was getting done. On top of that, a conflict that had been long lingering just below the surface popped up. And what would have been solved quickly in a chat exploded into a disaster.

She knew she needed to find a better way to lead remotely, but she wasn’t sure where to start.

Does that sound familiar?

Many leaders struggled (and still do) with their impact in a remote workplace. But since everybody hyped remote work, it was also difficult for the managers to discuss the fact that they were unsuccessful.

As a leader, you have many tasks on your desk to take care of. Still, in a remote setup, having in-depth conversations with team members about their work, performance, and development, tracking progress towards goals and objectives, providing support and guidance, resolving conflicts, maintaining a positive work environment, and fostering open communication can arguably become more challenging.

Understanding this list well is vital and (maybe also surprising) because it lacks one key thing often seen as the hardest to make up for, creativity. And creativity is impacted, but not in your leadership role because you’re not supposed to find creative solutions for the next pay cycle but be predictable to your people. You’re not supposed to find imaginative ways to communicate how your team achieve their goals, but be accountable for them.

And it’s so much harder to achieve that, I fully get that, if you’re not on the ground with the teams to observe what they do.

Now there are two parts to this. First, the question of how you can work with individuals. And secondly, how to track this for multiple teams. It is an important distinction, as the people’s goals will vary between their drive and the groups. On the one hand, people have personal desires, beliefs, and goals that shape their actions and decisions. These individual motives are often driven by self-interest and ego, leading people to act in their best interests.

On the other hand, people are also influenced by their social environment and the beliefs, norms, and values of the groups they belong to. This collective mindset can result in individuals conforming to group expectations and behaving in ways that align with the group’s goals rather than their own. The balance between individual and collective motivations varies from person to person and situation to situation, but both play essential roles in shaping human behaviour.

As a leader, you must be able to make decisions that serve both the interests of the individual and the group. This requires a deep understanding of the situation, the motivations of the people involved, and the possible consequences of different decisions. What’s difficult enough in an in-person setup, where there are plenty of opportunities for informal conversations and nonverbal cues that can give you a better sense of what is going on, gets painstakingly tricky in a remote setup, if not implemented with a very intentional approach to managing your relationships.

This article will discuss how you can best help individuals, build relationships, and maintain a reliable connection. In the next, we are going to take a look at teams.

Getting the most out of your One-on-Ones

In my opinion, the number one tool for working with your teams has always been one-on-ones. They are essential for team members to share their ideas and concerns and allow you to provide feedback and support. On top of that, by having regular, private conversations, you can get to know your team members more personally, which can increase trust, communication, and collaboration.

However, I often see that one-on-ones are only a checkbox on peoples’ calendars that they fulfil without a clear purpose. Lacking an agenda or not having goals for the meeting often makes those meetings unproductive, ineffective, and a waste of everyone’s time. Sometimes the manager also makes those sessions into their storytelling session, dominating the session, interrupting the team member, or not allowing the team member to share their thoughts and ideas, which is demotivation on top of the lack of outcomes. And finally, if you fail to follow up on commitments or action items discussed during the one-on-one, it can be frustrating and disheartening for the team member.

Especially if you have big teams with many directs of multiple teams, all those are traps easy to fall in, even more so in a remote setup, where the 15th face that pops up in a video conference for a one-on-one in a single week might not be able to easily motivate you to be at your best as the first.

One-on-One Remote Meeting Etiquette

The example for the 15th face in a video conference brings me to an essential part of how a one-on-one meeting should look in a remote setup. In the tools article 1, we talked about the infrastructure we will need, and for one-on-ones, two of them are especially important: Video conferencing and your whiteboard.

I said that for Video Conferences, it is necessary to respect people’s choices for keeping the camera off. This, unfortunately, does not hold for one-on-ones.

This call is not engaging

On the one hand, One-on-Ones are often discussing complex or sensitive topics. Without video, misunderstandings and miscommunications are more likely to occur. On the other, they are supposed to build a connection and provide insight into each other’s state of mind and level of engagement, which is almost impossible without visual cues.

Start with leading by example and turn on your video. If the other person is not turning theirs on, ask why to understand the reason and work on ensuring that both participants will have the video on in the future.

The other tool, as said, is the whiteboard. It will be your shared space to discuss matters and work together to visualise the topics you have discussed, track the action item and maintain the direction.

Have a dedicated board for every person you have one-on-ones with, and remember to review those boards between the meetings to ensure you remember all action items that might have been assigned to you.

This article will mainly focus on providing examples of using this whiteboard. You can find a template for the One-on-One Whiteboard, including all examples from this article, in the links. 2

Those examples help you to achieve the goal of getting the most out of your one-on-ones.

Staying organised and intentional

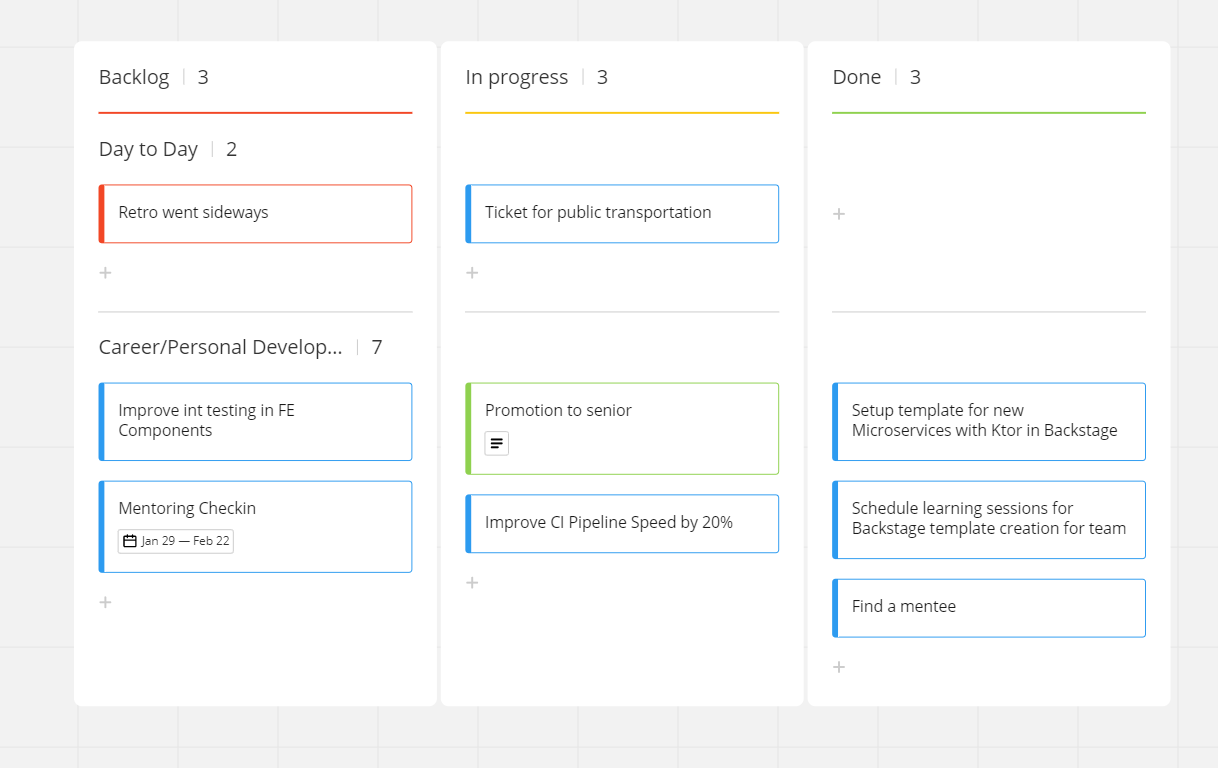

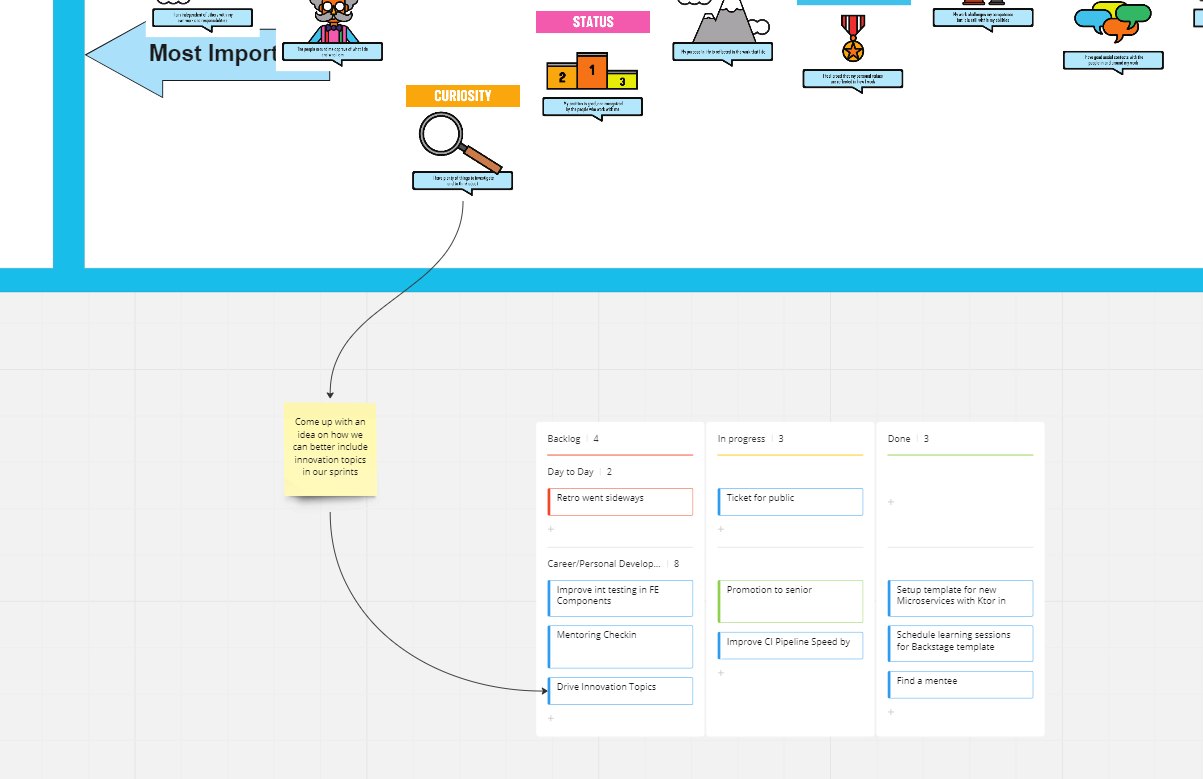

Being intentional, in that case, means being prepared. Make sure that for every one-on-one you have, you have the means to track what you were talking about, what your next steps are, and which action items you discussed. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, but I usually evolve my setup around a Kanban board with at least two swimlanes - Day to Day and long-term career/personal development.

Kanban Board on Miro For 1o1s.

The day-to-day swimlane acts as a backlog for topics that pop up during the week so that you and your peer can drop important but not urgent items and discuss them in the next session.

The long-term swimlane is about your peer’s long-term career/development plans and allows you both to track progress, thus giving you the means to provide your expectations early and clearly, and your peer an outlook on what they have to accomplish.

But how to get to the career development goals?

Identifying the Motivators

More often than not, career development is equal to job title ladders. That means that people are supposed to “climb up” the predefined setup in the organisation, from titles like Junior via Advanced to Senior, at some point perhaps deciding between a manager and expert path. Their development, however, is guided by the constraints of the organisation. And the titles act as extrinsic motivators for them. If this term is new, extrinsic motivators are external rewards or punishments like titles or pay raises. In contrast, intrinsic motivators are internal drivers, such as interest, enjoyment, and personal fulfilment.

While extrinsic motivators may act as a short-term boost to people’s happiness, their career path has to be aligned with what they genuinely want to ensure they stay motivated, satisfied and engaged. How to make this explicit, though?

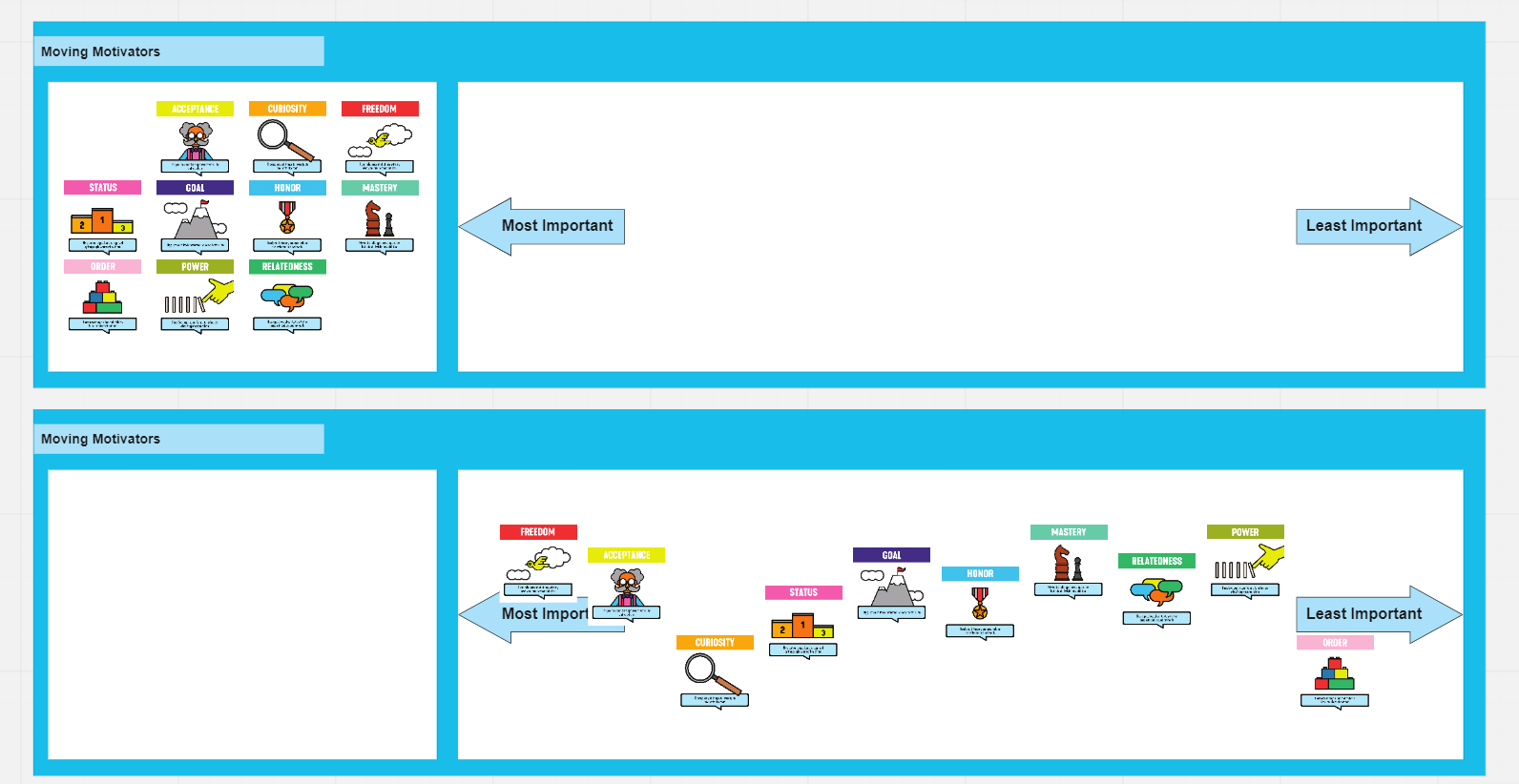

One exercise I found especially valuable in this context is the Moving Motivators from the book Management 3.03. The moving motivators exercise is a tool that helps individuals understand their internal drivers or motivators by identifying the values and activities that bring them the most satisfaction, fulfilment, and motivation in their personal and professional lives by moving ten cards that represent their motivators.

First, they order the motivators from most to least important. Next, based on a specific question, for instance, how is the current team setup impacting them, they can move single motivators up and down based on whether it is positively or negatively impacted.

Example of a Moving Motivator Exercise

I usually take a closer look at the elements in their top 5 motivators that are going down, and we try to create action items that we can directly derive from those motivators.

How a negatively impacted motivator can become an action item

This exercise has a positive impact on multiple levels. First, you know what possible demotivators are lingering about your team. Secondly, by addressing them, people know that you care about their well-being, improving their trust and thus their openness to share other problems with you in the future. And, by giving this task to them, you enable them to take care of and drive their well-being, motivating them even further.

Using the board from before allows you to track this element and ensure it is tackled.

Plan regular sessions for the moving motivators to ensure everyone is in a good place. Before or during changes, run specialised sessions with everybody in the team to see the impact of the change program and provide opportunities to influence it.

The career plan

Motivators, however, are no career plan. And creating one is extremely difficult for junior and senior people alike. A typical method involves steps from identifying career options that match your skills and motivators to making goals and measurements to track your progress. 4

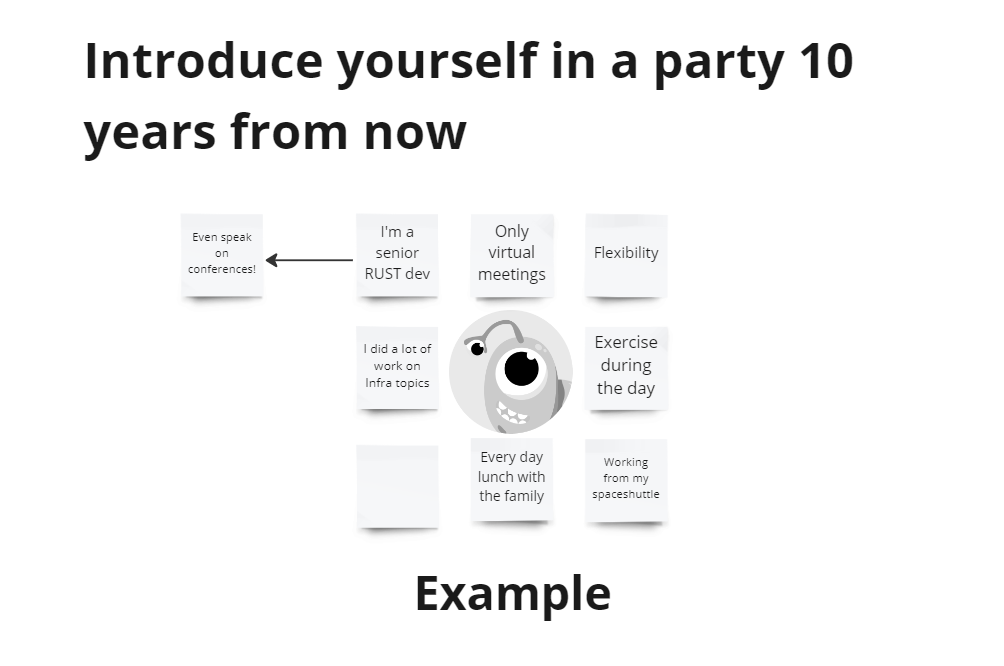

Most people are already overwhelmed with understanding where they want to be; thus, my first step is to run an exercise called “Party in 10 years”. It’s originally an icebreaker game, but one I found increasingly helpful to help people to identify where they want to be.

The Party In 10 Years exercise

The exercise is straightforward. You start a conversation at a party ten years in the future, and the person will talk about what they are doing now and how they got there. As ten years are far away, it seems much easier for people to go wide and think about their actual goals rather than just the following steps on the ladder.

Your job is to keep the conversation running, ask open questions, listen actively and write down what you hear on sticky notes. Once the person is done, quickly summarise what you heard and check if you have a similar picture.

From there, you can start bringing the things that came up to the kanban board. Talk openly about timelines and expectations. For instance, if the person is talking about a promotion, ask them when they feel ready for it, and provide your angle to it. Don’t commit to things you can’t promise, and be forthright about invisible walls that may keep the person from accomplishing their targets.

From there, you can directly start sketching out the expectations and next steps and bring them to the board so that you have a shared picture of how to continue.

Delegation Poker

Now that the person understands where they want to be next and has a plan sketched out how to get there, they will probably start running. First, however, a particular set of constraints needs to be addressed - the limits of what they can do and what you, as manager, feel comfortable having them do independently; in a nutshell, delegation. Delegation is the process of entrusting tasks, responsibilities, and authority to another person or group of people, usually intending to allow them to complete the job and learn new skills. It involves giving up control over a task or decision but retaining accountability for the outcome. The first part is easy, the second less so, even more so in a remote context where it’s harder to track what exactly everyone was doing.

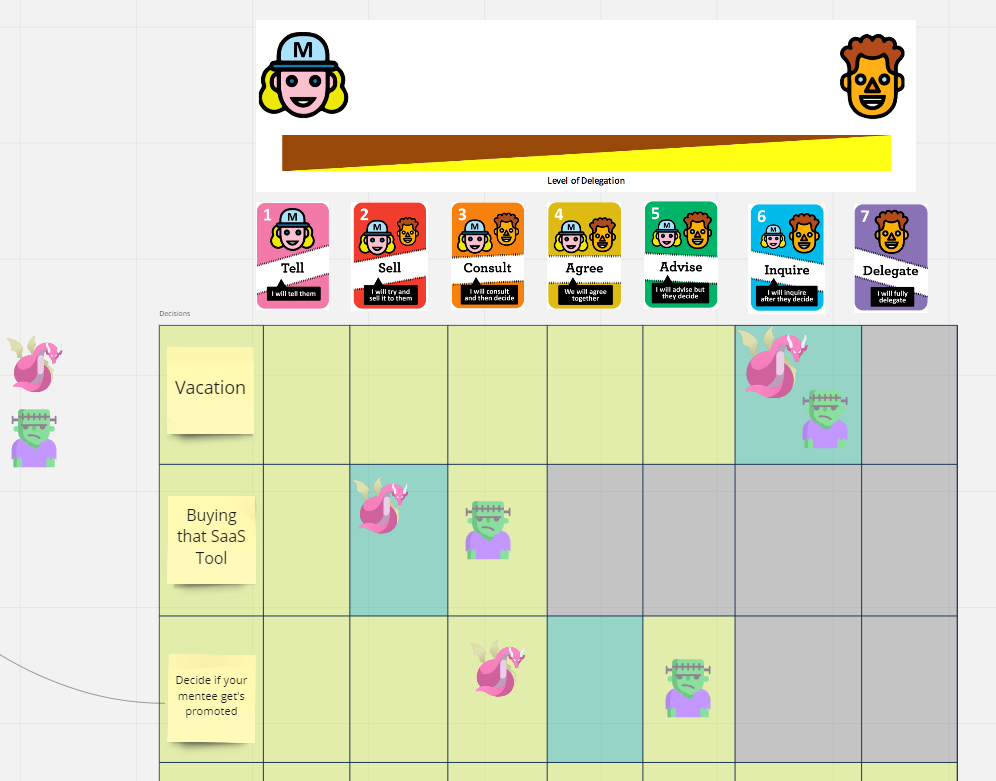

The tool I use to make this explicit is from the beforementioned Management 3.0 book, called Delegation Poker. It’s a small exercise in which the participants rank their willingness to delegate or take over specific tasks, highlighting constraints and clarifying expectations.

Let’s take vacation planning as an example: Who is going to take the final decision on when a person takes a vacation?

A delegation board with items on it

The first important step by the manager is to highlight any invisible walls. That is, constraints that are given that cannot be ignored. For instance, for vacation, the manager might be the one who clicks the approve button in the vacation planning tool, for which they have to be aware of the request. So fully delegating the task is technically not achievable.

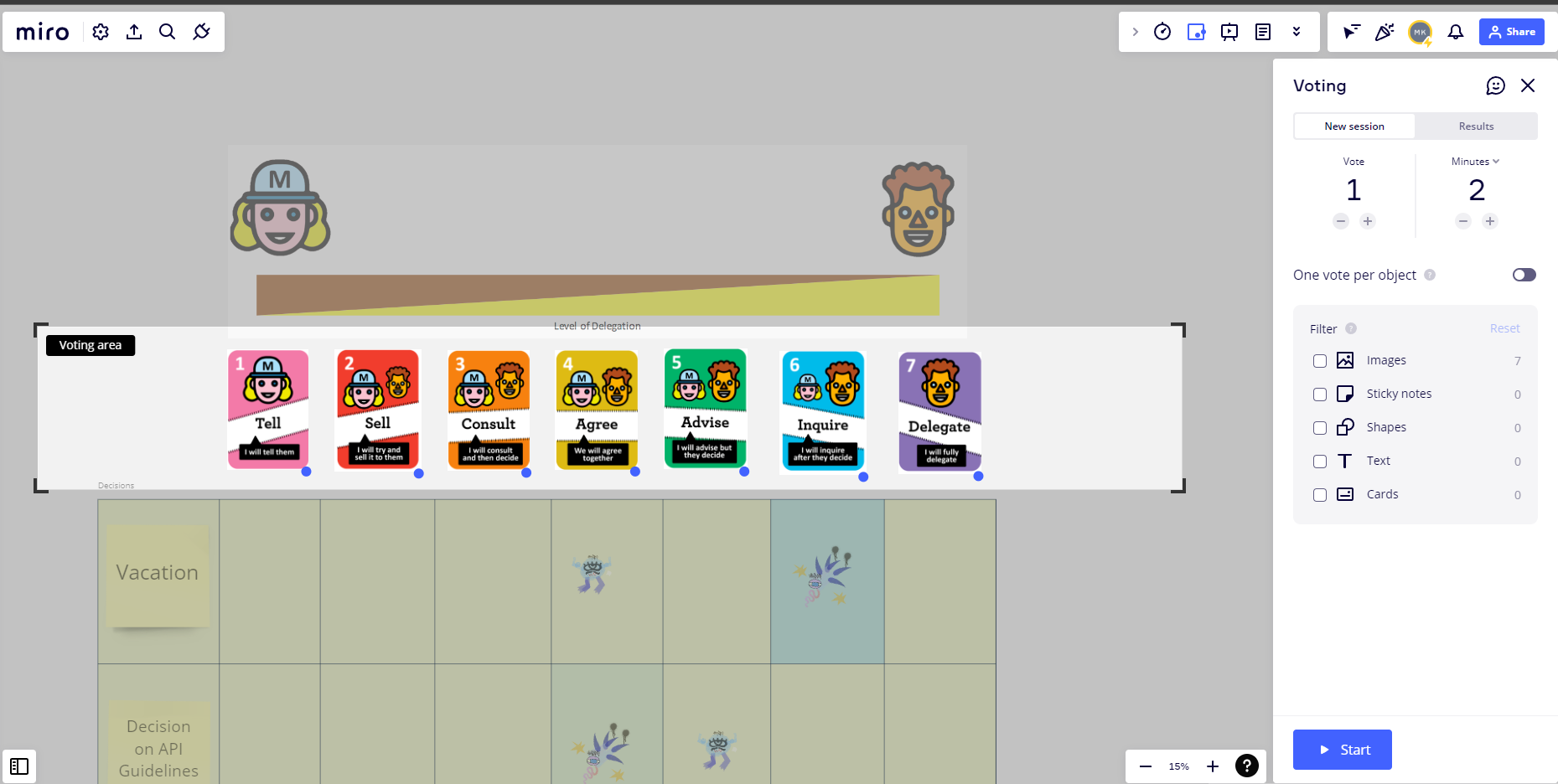

The next step is to vote for the level of delegation that each finds suitable silently. The voting can be done, for instance, with the voting tool that many whiteboard applications provide.

Setting up a voting session

After the voting, we compare how far we are apart. Then, both bring their opinion on why they selected a certain level, and then they do a second round of voting. After this round, the leftmost vote will be the starting point for the delegation, and the rightmost will be the target for the delegation. Then, we can derive action items on what we have to do to get there and challenge the manager’s view on how comfortable they feel with delegating certain elements and where they want to set walls or boundaries.

This visualisation has several elements I appreciate. For one, it shows the grey areas between don’t and do delegate and provides a more precise overview of the delegation level than, for instance, a RACI Matrix 5.

On the other hand, it has the power to shift more items to the right, which on the one hand, means that as a manager, you will have less on your table, and as managed that you can take more responsibilities and thus can grow in a very safe way and without high risk into running into certain escalation meetings, as hopefully the lines that will lead to them have been made explicit as invisible walls.

Making it last

The different elements we have discussed until now provide a good baseline, but more is needed to ensure that the conversations stay organised and intentional in the long run.

For instance, having a single element on your kanban for a complex career growth topic will only lead to misunderstandings and confusion in the long run. Instead, always think about and educate yourself on solutions that can help you become more deliberate. Remember, in the beginning, I said that we would have to formalise topics much more in a remote setup than in an in-person environment.

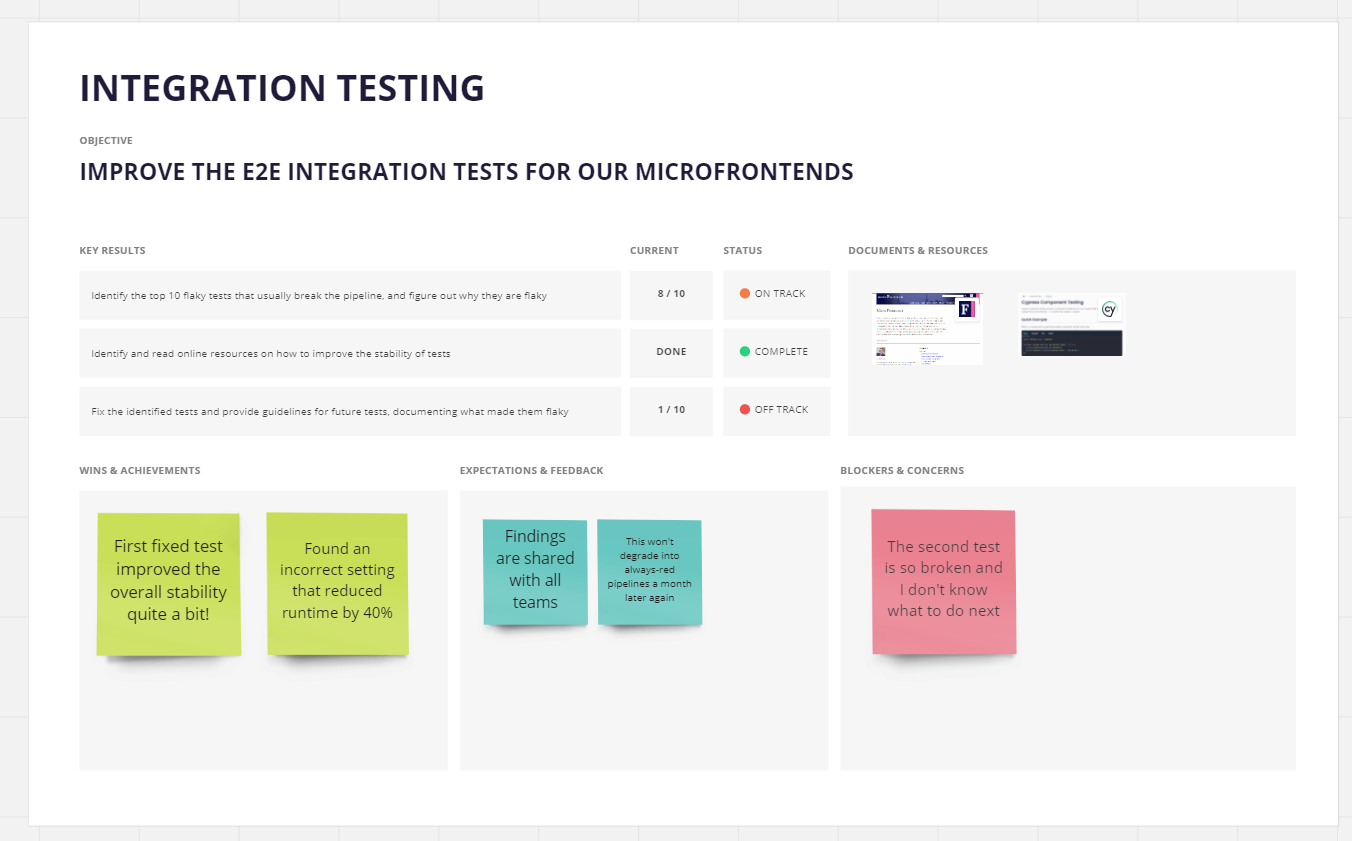

In the case of career goals, an example could be to add a personal OKR 6 template to the whiteboard.

Tracking development goals on a personal OKR board

On top of the headline, this allows both to track in more detail what the objective is about and what the expectations are. Also, it will show in writing how well specific goals have been accomplished.

Another thing is to receive feedback as a manager to get a feeling of how well you are doing. For example, I have written about how I measured myself in the past 7, and the re:Work survey 8 provides a great starting point for you.

Anonymously running those surveys is imperative because there is a difference in power in the one-on-one sessions. As a manager, if the person you are talking to doesn’t trust you, they won’t be motivated to give you honest and direct feedback. You will be given honest feedback only if people trust that you won’t hold it against them, and you can only be sure that the trust is there if the story people tell you in the one-on-ones and the answers from the anonymous surveys are fitting.

Difficult conversations

The hardest part of remote management had been the most challenging part of in-person already: Difficult conversations.

Difficult conversations are often about poor performance, team conflicts, personal issues affecting work or phases of intense stress and changing requirements.

As said, those conversations never were easy. Having them face-to-face, however, can make the messaging much more manageable. For instance, words you have not chosen wisely, given the circumstances, can be eased by visual cues and your body language.

In a remote setup, you have only your words and your face to deliver the message. As a result, it will be much easier for misunderstandings to arise and for context and information to be lost in transmission over a spotty internet connection.

More than ever, it will be essential for you to prepare. In Germany, a tool already used before remote work came in is called “kollegiale Fallberatung”, or “peer-reviewed consultation”. It refers to a process in which professionals from similar fields, for instance, managers, come together to discuss and provide support for a specific case or issue. It’s a way for colleagues to share their expertise and offer different perspectives to find the best solution for a complex problem.

Let’s say you have a conversation with a person who had a bad performance dip. You don’t want to demotivate them, but highlight that you expect more. In the peer-review consultation, you can first trial the situation in a role-game. Create a call with your peer group, select somebody who will act as the person you will have to talk to and ask the others to turn off their cameras and observe. Now you act out what you want to say to another manager, with others watching. The other person will try to act out their role as realistically as possible to ensure this will be a lifelike exercise for you.

After the conversation, everybody can give feedback on how it went, and you can take multiple iterations until you feel comfortable approaching the real talk.

With the feedback you acquire, you will gain many insights on how you can ensure that your message is coming out well, and you will also receive feedback on how the conversation will feel for the other and adjust your tone and words accordingly.

On top of it, you can record the call and rewatch it to make sure that a comment thought to lighten the dialogue up is not the final nail in the coffin for this particular conversation.

Don’t forget about the person

For now, the one-on-ones focus on creating value and being intentional and productive. But that’s not all life and work are about. Remember that the coworkers you have one-on-ones with are actual humans. So if you want to work together well, getting to know everybody on a more personal level is paramount.

I already talked in the last post about walking one-on-ones, which should be a part of your routine. Go for a walk with your mobile phone and talk about anything but work. You can even use a traditional phone with headphones. When walking together outside, it’s expected not to have eye contact always, so it’s not so different from a phone call.

Those little chats are important for you and your team and will help create empathy for one another and get your thoughts off the things dragging you down.

Ask the people in your team to plan those walking one-on-one sessions between themselves as well. Again, the more the people on your team know each other well, the better for the group’s health, as we will see in the next article.

What about Sarah?

With the help of these guidelines and tools, Sarah took a step back and re-evaluated her leadership style. She started by organising her one-on-one meetings, using a kanban board to track issues and progress. It helped her better understand what each team member was working on and how she could support them.

Next, Sarah used the moving motivators exercise to get a better understanding of what motivates each member of her team. With this insight, she could assign tasks challenging and engaging each team member, leading to increased motivation and productivity.

Sarah also used delegation poker to improve the delegation process. This helped her better to understand each team member’s strengths and weaknesses and delegate tasks more effectively. The delegation poker also helped her team members feel more empowered and take more ownership of their work.

Finally, Sarah trained herself in difficult conversations with a peer. This helped her be better prepared for conflicts and approach tough conversations with empathy and a solution-focused mindset, and she was much less scared that those might come up.

With these changes in place, Sarah noticed a positive shift in her team. Meetings were more productive, communication was more transparent, and the team was more motivated and engaged. And when the conflict popped up, she could handle it quickly and effectively without escalating into a disaster. As a result, Sarah felt more confident and in control as a remote manager, and her team thrived.

Doesn’t that sound like a lovely place to be in? Well, it’s only a story, so don’t get excited. But let’s work on achieving some parts of it, shall we?

The following post will take a little as my calendar is staffed (god, I’m so bad at delegation, I wish someone would write a blog post on a tool I could use for that…), so follow me on linkedin to get a notification when it’s finally ready for you!

-

Making remote leadership work Part II: The minimum toolset · matthias-kainer.de ↩︎

-

Amazon.com: Management 3.0: Leading Agile Developers, Developing Agile Leaders (Addison-Wesley Signature Series (Cohn)): 0785342712476: Appelo, Jurgen ↩︎

-

(The impact of Covid on my leadership style · matthias-kainer.de)[https://matthias-kainer.de/blog/posts/impact-on-leadership-in-a-pandemic/] ↩︎

-

(re:Work - Guide: Give feedback to managers)[https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Xhos_gEauxXtUyPQ2V3qrUciu7yudCAZVtHCLVlPJe4/edit] ↩︎